By Ranu, Economist

Rammohan is a gardener,( maali), who visits my parents’ house once a week to take care of their garden. He does similar work for other houses in the locality, earning around 6,000 rupees a month, which totals 72,000 rupees a year. In statistical jargon, Rammohan is a self-employed individual or an own account enterprise (OAE). This means he works for himself, earning a fixed monthly wage but without access to paid leave, social security benefits like provident fund (PF), gratuity, medical facilities and, a written job contract. Like many other gardeners, maids, mechanics, tea and vegetable sellers etc., Rammohan is also a part of India’s vast informal sector.

***

We often ask this question - why we should care about workers such as Rammohan? After all, they provide us services at cheap rates and make our lives more convenient and gradually they will also benefit from the trickle down effect. Moreover, this vast informal sector does not seem to be causing any harm to India’s economic growth, with real GDP averaging a strong 6.5% annually over the past two decades.

But if India needs to grow faster, to be able to achieve the high-income status like South Korea, Japan, US and the UK, it needs to grow by 8% over the next decade. This faster economic growth can only come if our consumption and investment increases. To achieve the former, India needs to provide more quality jobs or formal jobs which in turn increase the incomes, thereby, pushing up consumption of goods and services. This would also attract more investment in the economy, as companies are likely to expand in response to a promising outlook where more people can afford their products.

However, if India continues to add thousands of uneducated/unskilled and low-paid workers to the already large informal sector – which accounts for half of the total employment in the country – it will be difficult to achieve the upper-middle-income status in the next 10 years, let alone becoming a high-income country by 2047, which is the Indian government’s ambitious target.

In this context, I should be applauding the recently released preliminary survey results for the informal sector (conducted by India’s statistical agency), which show a decline in the sector’s contribution to the country’s total output (gross value add/GVA) from 9.2% in FY16 (April 2015-March 2016) to 6.3% in FY231. Theoretically, this suggests an expansion of the formal sector, where jobs come with social security benefits (like PF, gratuity) and a written job contract.

But the reality is quite different! This decline in the informal sector is not leading to an increased size of the formal sector. Surprised? Let’s try to understand the reality.

Understanding the realities of India’s vast informal sector

Few economic analysts have been celebrating the ‘shrinking’ of the informal economy, but this celebration is premature. There are some troubling facts, which have not been covered by these analysts.

Firstly, the Survey for the informal sector covers informal enterprises only in the manufacturing and services sectors, leaving out the largely informal agriculture and construction sectors. Agriculture is fully informal as it is not taxed and, more than 80% of employment in construction activities is concentrated in informal enterprises. Upon combining the gross value add (GVA) output of all these sectors – manufacturing and services informal enterprises, agriculture and construction – the size of the informal economy is estimated to be roughly 33% of India’s GVA in FY23 (Table 1). This is lower than the 36.2% share of GVA in FY11, thus, reflecting that the informal economy has reduced. But this decline has come when GVA share of only informal manufacturing and services enterprises has been taken into account, leaving the GVA shares of agriculture and construction sector, which has increased.

Table 1: Size of the informal economy

|

FY11 |

FY16 |

FY22 |

FY23 |

|

|

% share in India’s gross value add |

||||

|

Share of manufacturing and services informal enterprises in the economy |

8.9 |

9.2 |

6.2 |

6.3 |

|

Share of agriculture |

18.4 |

17.7 |

18.9 |

18.2 |

|

Share of construction |

8.9 |

7.9 |

8.5 |

8.8 |

|

Share of informal economy |

36.2 |

34.8 |

33.6 |

33.3 |

Source: MoSPI, RBI

Secondly, the increased GVA share of agriculture is a cause of concern because it signifies a backward shift from the formal and modern sectors of manufacturing and services to the low paying agriculture work. This backward slide is further evident in the increased employment share of agriculture, from 41% in FY19 to about 45% in FY23. India’s agriculture sector already has a larger than usual share of total employment compared to other developing economies where the average employment share in the agriculture sector was about 25% percent in 2023.

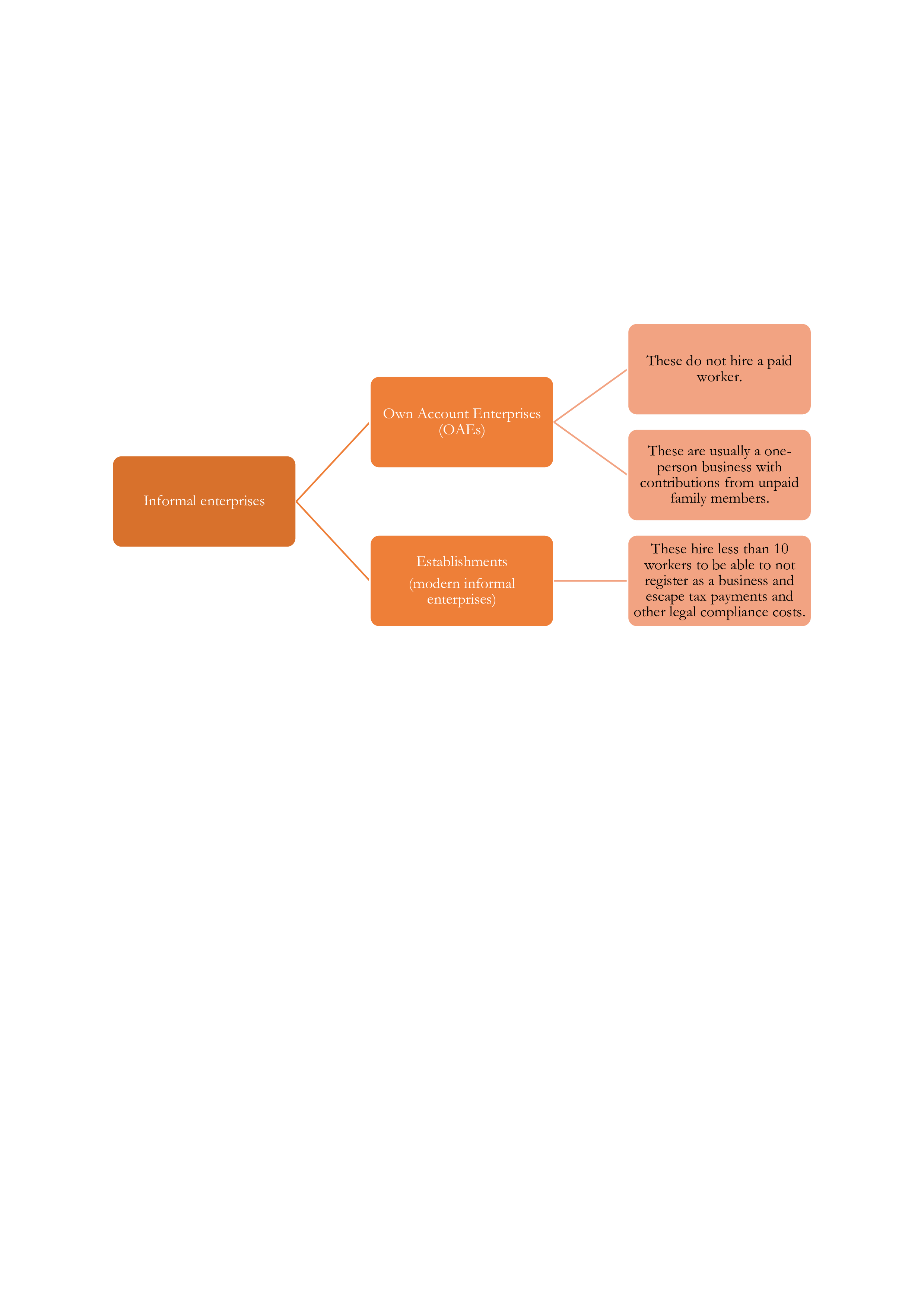

Finally, in very simple terms, the informal enterprises are of two types – OAEs like Rammohan and ‘Establishments’ that hire paid workers. These ‘Establishments’ offer better incomes and, are more efficient and modern compared to Rammohan OAEs. However, the informal ‘Establishments’ have declined in number, damaged by the 2016 demonetization and the hastily implemented GST reforms in 2017. As a result, the GVA share of these informal ‘Establishments’ in manufacturing and services enterprises has declined over the last decade, primarily due to the reduced number of informal ‘Establishments’. In contrast, the Rammohan kind of OAEs, which account for more than 80% of the informal enterprises, have increased massively since FY162 but they provide very low incomes and are extremely inefficient.

Types of Informal Enterprises

Therefore, even though the size of the informal economy has shrunk, it has been accompanied by a backward economic shift to agriculture and a decline in more efficient informal enterprises or ‘Establishments’. So, it would be wrong to state that the workers who lost their jobs, due to the closure of modern informal enterprises, have found formal jobs, because, the share of formal jobs have also declined since FY18.

Serious lack of good quality jobs in India

There are 371 million youth in the country, and most face an uncertain future due to low-income jobs and limited prospects of moving up in the society due to a serious lack of good quality jobs or formal jobs, which come with social security benefits, written job contracts and regular monthly salary. Unfortunately, such jobs are scarce in India and have declined since FY18. The share of jobs that ensure a fixed or regular income every month has declined from 23% in FY18 to 21% in FY23. Moreover, more than half of this small share of regular paying jobs did not provide access to social security benefits in FY23.

Clearly, workers who lost their jobs in the modern informal enterprises (or Establishments) did not find formal jobs. So, where did they go? They have either shifted back to agriculture or become self employed by forming Rammohan kind of OAEs2. Some have even left the workforce, discouraged by the lack of job opportunities (refer to the recent ILO report for a detailed analysis of India’s labor market challenges3).

A tale of two Indias

This vast informal sector, marked by low incomes and a lack of good quality jobs, has given birth to two Indias. People like us, who have gone to reasonably good schools and are earning well enough to shop in malls, live in the shiny new India but people like Rammohan live in the old, poor and rundown India. The problem is that these two Indias are not converging, resulting in deepening income and wealth inequalities in the country.

A typical informal worker in an informal enterprise earns 63% of India’s annual per capita income (GDP of India divided by its total population, which was Rs 1,95,914 in FY23). Almost 18% of total employed workers in the country earn this meager amount every year. What is alarming is that the proportion of per capita GDP earned by these workers has fallen from 79% in FY16 to 63% in FY23. Additionally, workers in the agriculture sector, which holds 42% share of total employment in India, earn just half of the annual per capita income5.

Therefore, the per-worker incomes in the informal enterprises not only increased at a significantly slower pace compared to average national income but they also remain substantially lower than the national per capita income, which is primarily driven by the top 10% income earners. This means that more than half of India’s workforce is living on earnings just sufficient for survival. Given this context, is it possible for India to fulfill its ambitious goal of becoming a high-income country by 2047, without addressing this serious challenge?

Conclusion

So, despite the recent newspaper articles claiming a reduction in the informal sector, the reality tells a different story. The informal sector remains substantial, with significant contributions from the agriculture and construction sectors that are excluded from the official survey of informal enterprises. The overall decline in the informal sector's share of total output masks deeper issues, such as the increasing dependence on agriculture and the shrinking output of more productive informal enterprises.

Addressing these issues requires a complete understanding of the informal sector, which can only be achieved through improved coverage and increased frequency of surveys of informal enterprises. Equally important is the acceptance of survey results, no matter how uncomfortable they might be.

Footnotes

1 This survey – called the Survey of Unincorporated Enterprises – is conducted by India’s statistical agency every five years and covers informal enterprises in the manufacturing and services sectors.

For the ease of understanding I have referred to all annual data in terms of India’s fiscal years, which runs from April to March next year. However, the Survey of Unincorporated enterprises and the RBI’s KLEMS dataset cover annual data from July to June next year – that is, 2015-16 refers to July 2015 to June 2016 period. The difference between the two is not significant for the purpose of this article. Also, all calculations in this article are for nominal values as it would have been difficult to deflate (adjust for inflation) the survey values.

2 The employment share of self-employed workers (or OAEs from the enterprise perspective) has increased from 52% in FY18 to 57% in FY23. This statistic is sourced from the Annual PLFS survey conducted by NSO.

3//www.ilo.org/sites/default/files/wcmsp5/groups/public/@asia/@ro-bangkok/@sro-new_delhi/documents/publication/wcms_921154.pdf">https://www.ilo.org/sites/default/files/wcmsp5/groups/public/@asia/@ro-bangkok/@sro-new_delhi/documents/publication/wcms_921154.pdf

4The percentage share of such enterprises in total informal manufacturing and services enterprises fell from 15.8% in FY16 to 14.9% in FY23.

5 The earnings for agriculture sector is an approximation. First, calculate per employed worker agriculture and allied sector GVA from the KLEMS database of the RBI. Second, use the labor income share provided in the KLEMS database to arrive at an annual earnings figure for an employed worker in the agriculture and allied sector.