By Ranu , Economist

Investment is the beating heart of the economy, pumping life into every sector. It creates quality jobs, raises incomes and boosts consumption. Investment also drives innovation and productivity growth, which are critical for long-term economic growth.

It is for these numerous benefits that all eyes are on the investment activity in India. For a low-middle income country – amongst the ranks of Pakistan, Bangladesh, Sri Lanka, the Philippines, and Viet Nam – India needs higher investment. Unfortunately, the investment to GDP ratio declined from a peak of 36% in FY08 (April 2007-March 2008) to 29% in FY20. This implies that investment grew at a slower pace than GDP or total output in the country.

The reasons underlying the weakness in investment activity are varied, starting with the end of easy and cheap foreign money flowing into India following the global financial crisis in 2008-09. Thereafter, five years of policy paralysis under the UPA-II government, ten years of unsustainable levels of bad loans with the commercial banks, policy shocks of demonetization and GST reforms, as well as increased economic policy uncertainty, weighed on investment growth.

Recently, however, Indian analysts and economic commentators have been celebrating a supposed renewed vigor in investment activity. Economic optimism is said to be at a multi-year high, the government’s investment push has supposedly reached massive proportions and, investment in residential property has surged. And given how the balance sheets of commercial banks have been cleaned up of bad loans, a boom in private corporate investment is surely just around the corner!

But remarkably, this optimism and the supposed surge in government and real estate investments is not entirely visible in the official data (released by India’s statistical agency). Moreover, investment in India remains disappointingly weak compared to other developing economies, especially in the manufacturing sector and in the private corporate space.

Public investment growth: overemphasized in the post-pandemic period.

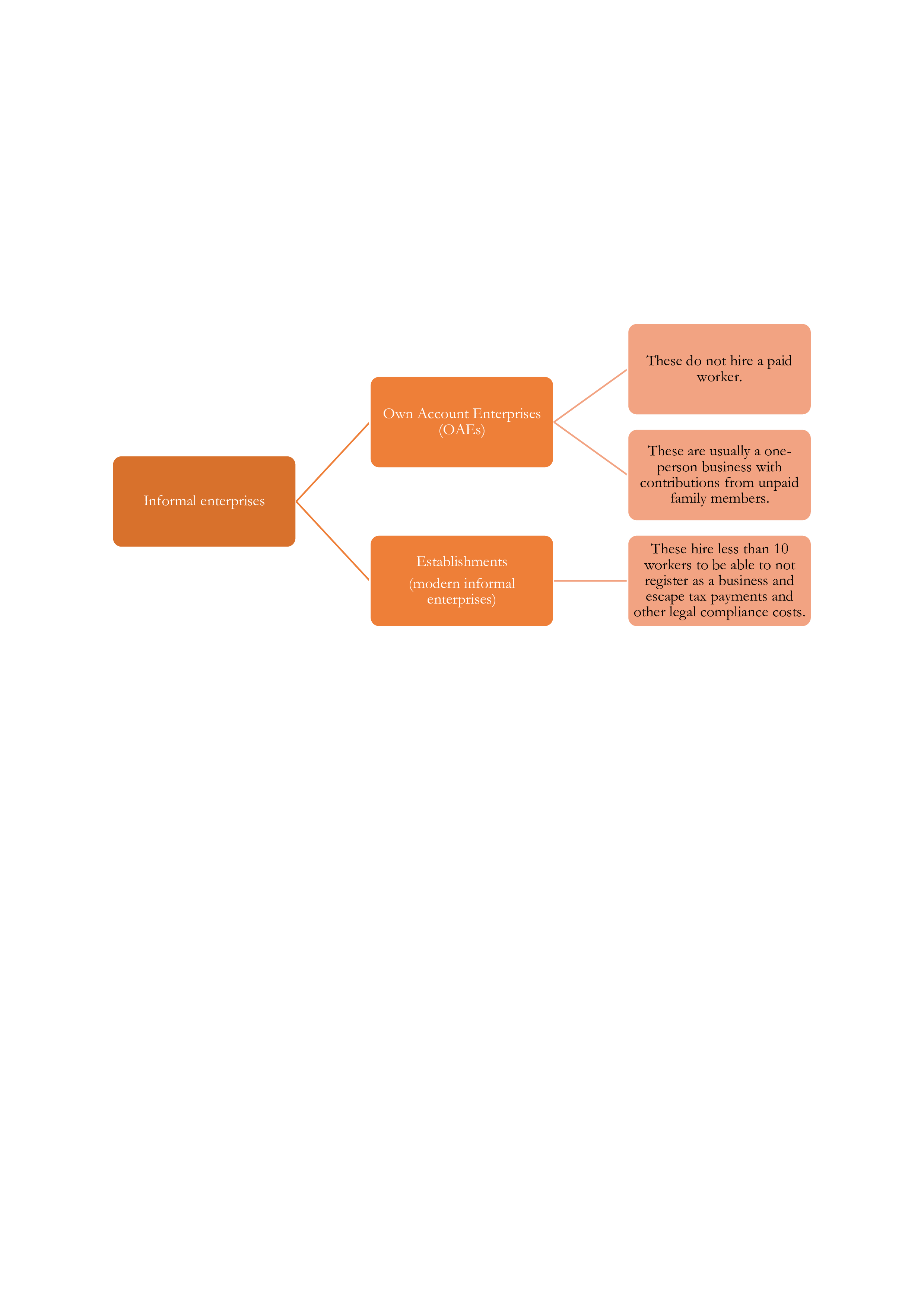

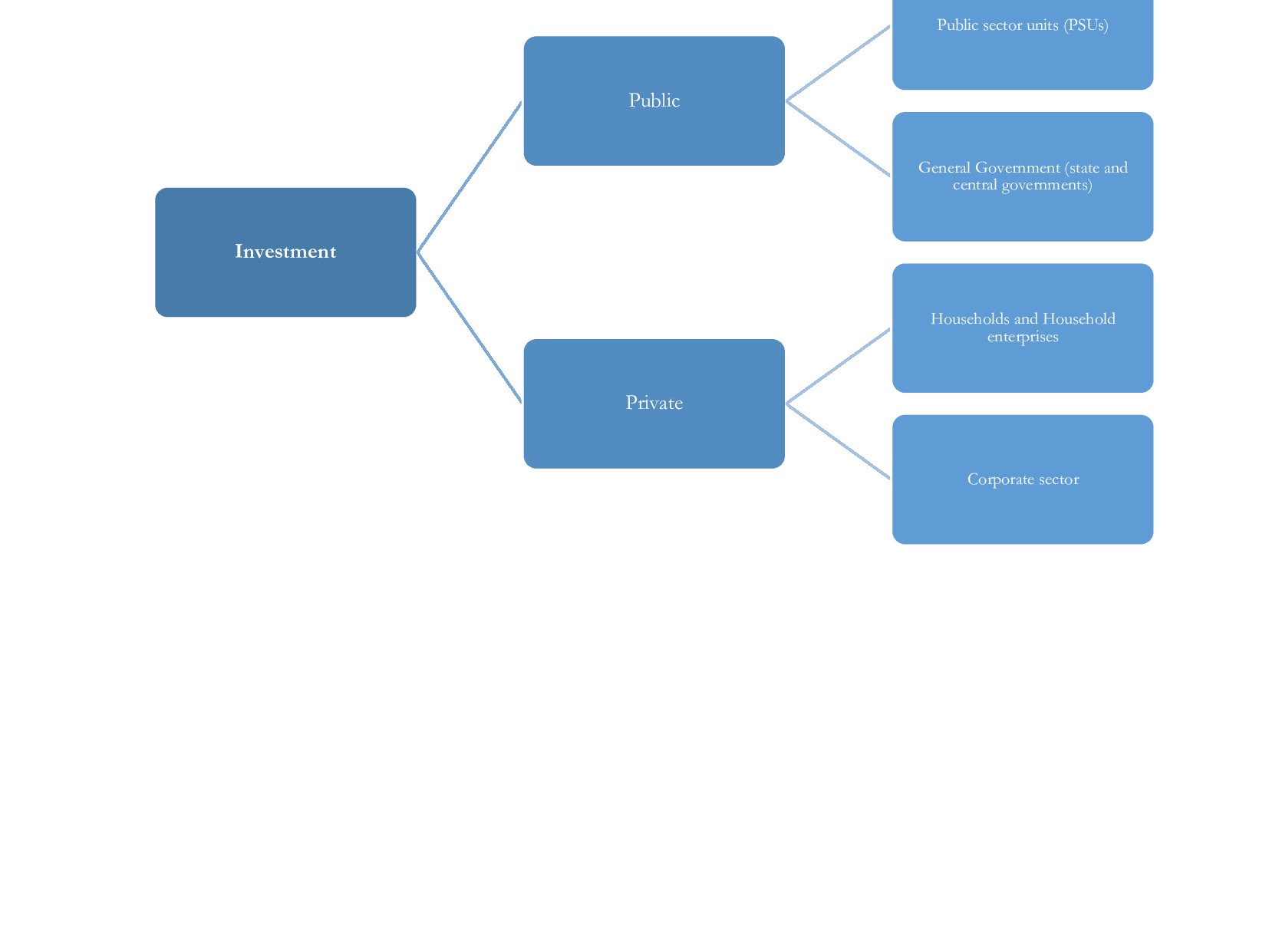

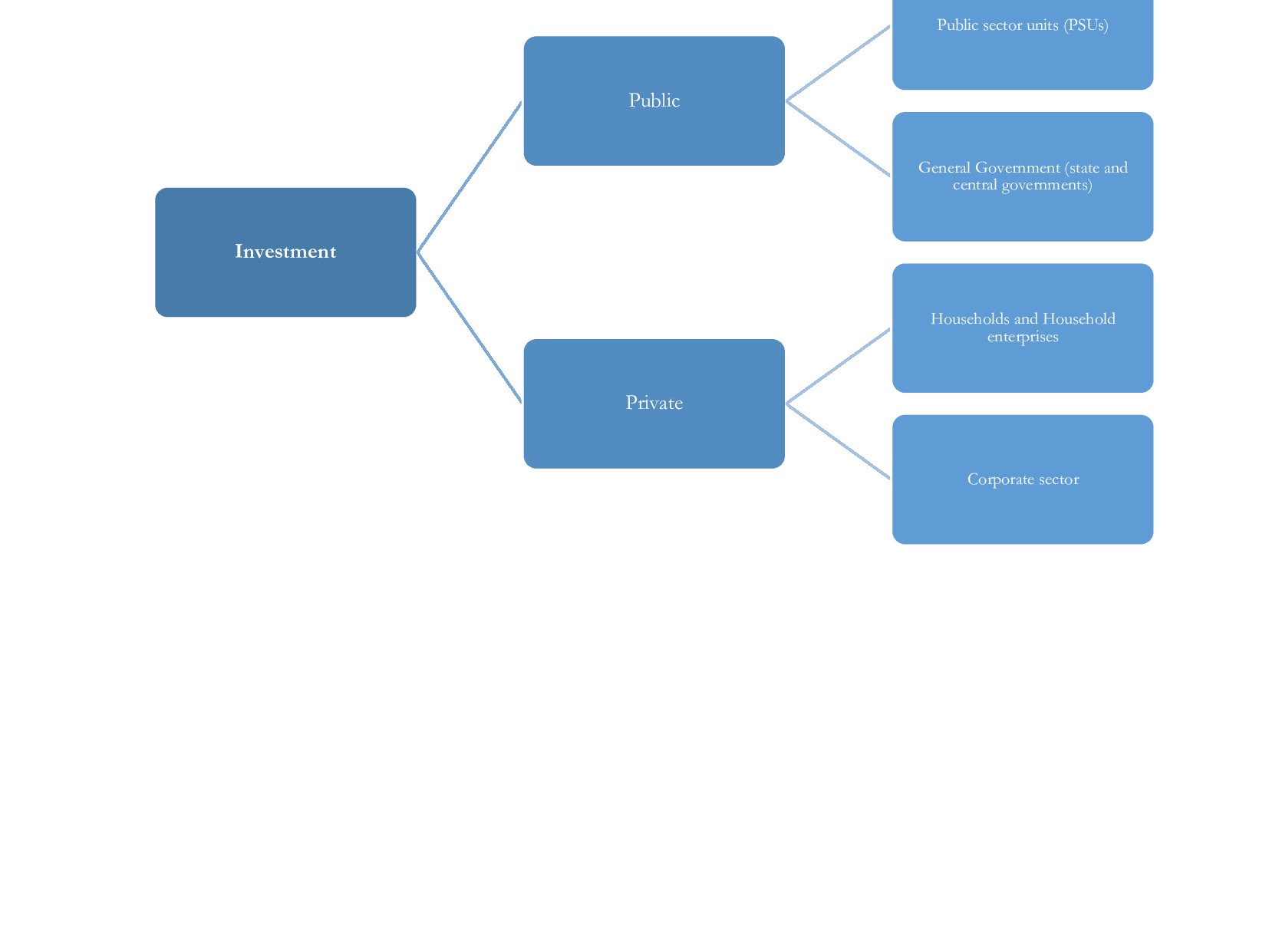

It is true that the GDP share of investment has increased – from 29% in FY20 to 31% in FY23. But this increase was not driven by the supposed surge in public investment (Refer to Figure 1 for the components of investment and for more details read footnote i).

Figure 1: Components of investment

Public investment comprises of spending by public corporations or PSUs (such as ONGC, BHEL etc.) and the general government (state and central governments). Between FY20 and FY23, the GDP share of investment by public corporations declined from 3% to 2.9% but the GDP share of government investment slightly increased from 3.6% to 4.1%. Combining both the components, public investment increased its GDP share only marginally, from 6.6% to 7% (refer to footnote ii for details). This might be confusing because economic commentators have highlighted the spectacular growth rates of government investment – for instance, growth of 31% in FY23. But what matters is the size of the investment with reference to the size of India’s economy. It is similar to throwing two buckets of water in a pond compared to one bucket yesterday. Even though it is a growth of 100% in the number of buckets, the addition of one more bucket of water would still be small as a share of water in the pond.

Contrast this performance of public investment with that of private investment, which has been instrumental in driving up the GDP share of total investment. The GDP share of the private investment increased from 22% in FY20 to 24% in FY23! But does this mean that private corporate investment has been rising? No it does not.

Private investment has increased due to a jump in household investment.

Private investment includes investment activity of: (a) corporate sector or the formally registered companies (like the Infosys, Tata and Reliance conglomerates, Ruchi Soya etc.) and; (b) households and household enterprises (HHs hereafter).

Private corporate investment has maintained its share of GDP at 11% but it is the GDP share of investment by HHs that has increased significantly from 11% in FY20 to 13% in FY23. So where are HHs investing?

The informal sector is expanding.

Investment by HHs in real estate has hardly increased – the share in GDP was 4.2% in FY20, which increased to 4.7% of GDP in FY23. Real estate remains the largest investment category for the HHs, but its share in total household investment has declined over the last decade – falling from 52% in FY14 to 36% in FY23. This significant weakness was caused by the massive slow down in the real estate sector due to the global financial crisis – real estate projects stalled as companies had taken on too much debt from commercial banks, which in turn led to a surge in bad loans and a sharp fall in credit availability in India.

Instead, over the last decade, HHs have invested more in agriculture, manufacturing and services. But how can a household invest in manufacturing or services?

Households in statistical jargon consist of not only family based households but also small unregistered businesses that form the informal sector in India. Think of a small papad and pickle production unit operating out of a house (manufacturing) or your trusted vegetable vendor around the corner (trade services) or an auto rickshaw driver (transport services) or a small tea shop (hospitality and restaurant services). When these businesses invest in new tools to make pickle or buy a brand new auto rickshaw or buy some benches for the tea stall, it gets recorded as household investment in manufacturing, transport and hospitality services.

The GDP share of HH investment in agriculture, manufacturing and trade services, increased from 3.9 % in FY20 to 4.8% in FY23.

But then what about those analysts who keep on writing that Indian households are investing or saving more in physical assets?

Household investment in physical assets is not the same as investing in real estate.

Yes, HHs have been saving or investing in a lot more physical assets, which is termed as ‘dwelling, buildings and other structures’ in statistical jargon. But this does not necessarily mean residential real estate property! A large part of physical assets is non-residential, comprising of tea stalls, mechanic shops, road-side dhabas etc. So, yes, as the economic commentators have been highlighting, investment of HHs in physical assets increased from 7.2% of GDP in FY20 to 9.2% in FY23. But 75% of this increase came from HH investment in non-residential physical assets in the informal sector.

But why is increased investment in the informal sector problematic?

Expansion of informal sector at the expense of the private corporate sector will lead to lower growth in the future.

Productivity levels in the informal sector are significantly lower compared to the formal corporate sector. So increased investment in the informal sector would lead to its expansion, which will depress the productivity levels of the overall economy, promote inefficient use of resources and weaken human capital development due to lower incomes and increased forms of vulnerable employment (such as tea sellers, fruits and vegetable vendors etc.). This will lower India’s long-term growth. Therefore, increased investment in the informal sector is bad news for India and also reflects the inadequate investment by the private corporate sector.

Private investment in India has disappointed compared to other developing economies.

Private investment is important for enhancing market competitiveness, boosting innovation, increasing labor productivity levels, and creating jobs. But private investment has declined in India. After achieving a peak share of 30% of GDP in FY08, India became a low-middle income country (LMIC) in 2009. Thereafter, the share fell to 21% of GDP in FY20. It has, however, improved to 24% in FY23.

Compared to other developing economies, India has lagged in private investment activity. Not only has the GDP share of private investment declined over the years, which is in contrast to the experience of other major developing economies, it is insufficient for a large and diverse country like India. Consider a few major middle-income economies:

- Viet Nam achieved the LMIC status in 2011, two years after India transitioned to LMIC. Since then the GDP share of private investment in Viet Nam has consistently increased from 15% to 20% of GDP.

- Bangladesh recently transitioned to LMIC in 2015. Private investment to GDP ratio has increased from 22% in 2015 to 25% in 2022

- Malaysia was a LMIC in the 1990s (graduated to upper-middle income economy (UMIC) in 1998), the share of private investment in GDP increased from 22% in 1990 to 32% in 1997.

- China became a LMIC in 1998 when private investment to GDP ratio stood at 30%, which increased 39% in 2011. China transitioned to UMIC in 2012.

India has also invested considerably less in the manufacturing sector. While in 2022, Viet Nam invested 8% of its GDP in manufacturing and Malaysia invested 19% of its GDP, India invested just 5% of its GDP in the manufacturing sector in FY23. And this share has declined since FY10 (6%). Despite the much publicized production linked scheme (PLI) and Make in India campaign, Indian government has failed to incentivize private investment in manufacturing. This sector is very important for India’s future growth as it has the potential to create more jobs (specifically labor-intensive sectors) and boost productivity levels in the economy.

India has a long way to go to increase productive private corporate investment.

Increased investment by the private corporate sector is a must for higher growth and more jobs in the future. That requires policy certainty, economic openness, big-ticket reforms and improved growth outlook.

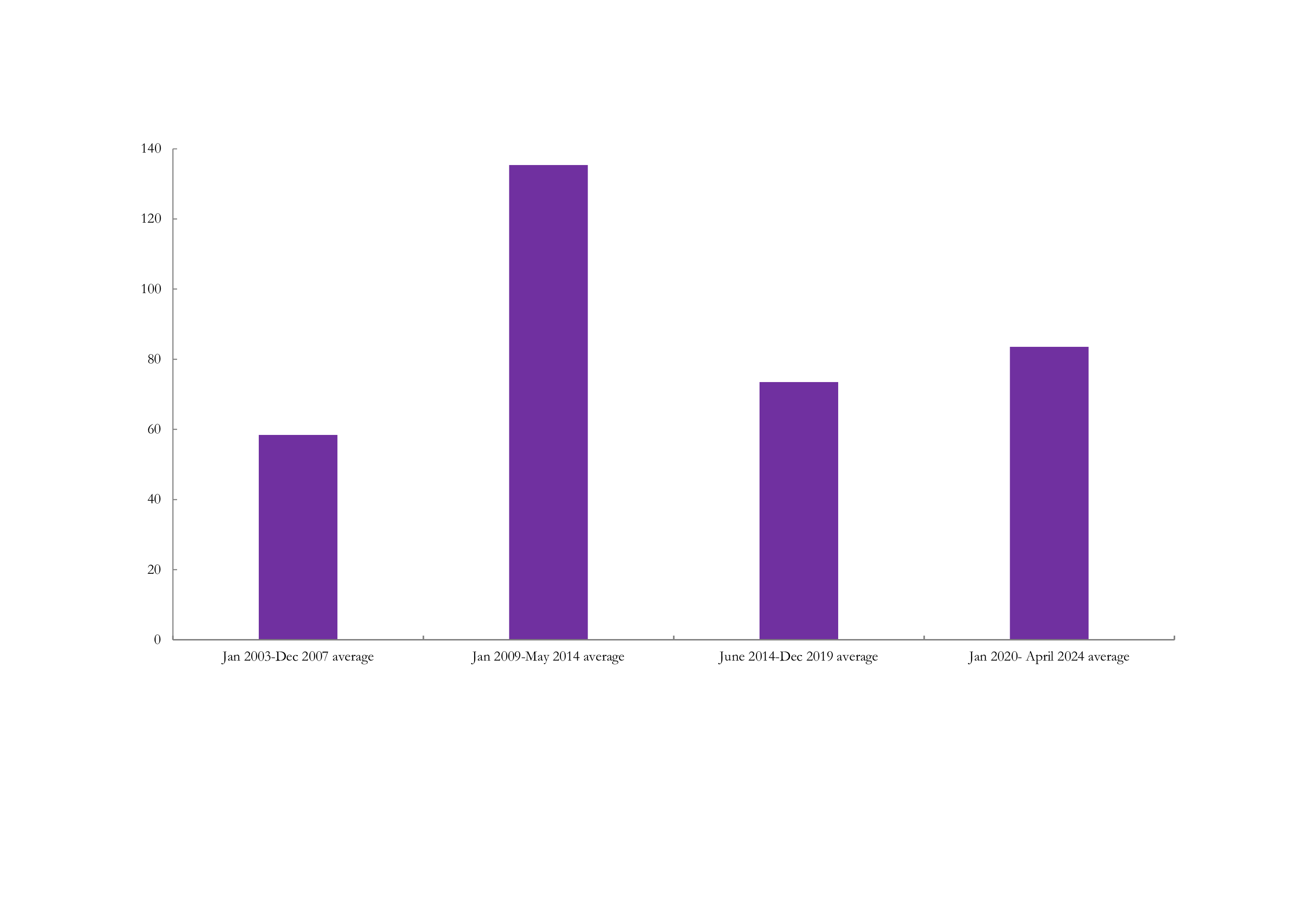

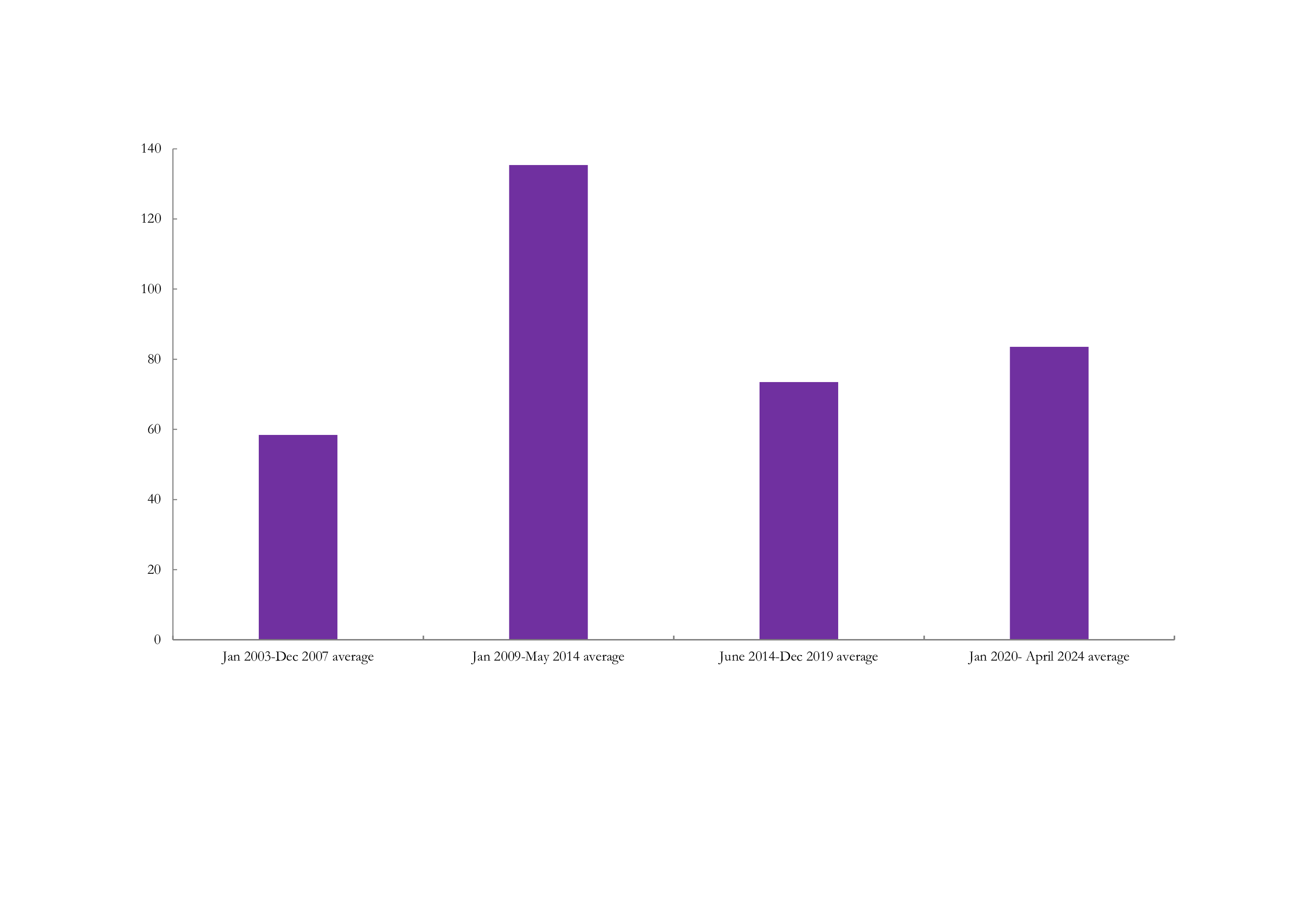

Policy uncertainty has increased over the last few years (Figure 2). During the golden years of investment, policy uncertainty was low and the share of private corporate investment in GDP increased from 6% in FY03 to 19% in FY08. The policy uncertainty index shot up during 2009-14 due to policy paralysis and rise of bad bank loans, which crushed private corporate investment activity in India. This situation was corrected somewhat between 2014 and 2019, when policy uncertainty declined significantly. But overall policy uncertainty remained higher compared to the 2003-07 period. Since 2020, policy uncertainty has further risen and the GDP share of private corporate investment has declined to 11% in FY23 (refer to footnote iii for details).

Figure 2: Policy uncertainty has increased and is higher than the golden period for private corporate investment during 2003-2007.

Source: https://www.policyuncertainty.com/india_monthly.html, authors’ calculations

India’s economy has become less open in a bid to build its manufacturing sector. Post-2014, tariff and non-tariff barriers have been raised to encourage domestic manufacturing, on the back of Atma Nirbhar Bharat and Make In India campaigns. Between 2014 and 2018, average tariff rate increased from 13% to 18%. This is higher than the rates in China (7.5%), Viet Nam (9.6%) and Bangladesh (14.1%). As this article highlights, various policy initiatives and campaigns to boost manufacturing in India have not been effective, with investment in the sector barely increasing from 4.6% of GDP in FY20 to 4.8% in FY23.

A few important reforms, that can boost growth and investment, have been ignored or shelved – significant barriers to foreign direct investment in the services sector need to be removed, labor market regulations should be simplified and eased, land administration and acquisition needs to streamlined and reformed, access to basic infrastructure like water and power supply needs to ensured.

Moreover, the recent remarkably high GDP growth rates, due to statistical and methodological peculiarities, mask a weak growth outlook and a slowdown in private consumption growth. This is evident in the tone of the private corporate earnings calls, during which the top executives raised concerns over GDP growth estimation, sector’s limited private investment plans and weak consumer demand in rural areas (https://indianexpress.com/article/business/economy/as-india-inc-commends-gdp-growth-some-concerns-private-capex-sluggish-rural-demand-9331772/#:~:text=As%20India%20Inc%20wraps%20up,in%20private%20capital%20expenditure%3B%20and). Weak growth outlook signifies lower returns on investment for the private corporate sector.

Economic analysis requires patience and attention to detail.

Off-hand commentary on shallow analysis of investment hurts the prospects of Indian economy. While economic commentators and market analysts might win brownie points with the government for their optimistic coverage of investment and growth in the country, their imaginative commentary cannot replace the reality on the ground.

If investment activity was genuinely strong then data would have shown more quality jobs and higher private consumption growth. Instead, since 2020, the numbers of self-employed workers (such as the tea sellers, vegetable vendors and rickshaw pullers) have increased, reflecting the sorry state of India’s job market. Incomes of people have stagnated and private consumption has grown at a slow pace.

To secure its economic future, India must commit to substantial structural reforms that will create an environment favorable for private corporate investment.

***

Footnotes

- Investment can be broadly categorized as public and private. Public investment includes central and state governments as well as public sector units (PSUs). Private players include the corporate sector and, households and household enterprises.

While government investment involves building roads, ports, school infrastructure etc, private corporate investment and investment by PSUs comprise of factories, equipment or machinery, office buildings etc. This kind of investment is essential for India’s development and transition from a low-middle income country to a high-middle income country like Malaysia, China and Chile are.

Conversely, investment by households and household enterprises (HHs) include agriculture equipment like tractors and electric threshers, auto rickshaw and taxis, a make-shift tea shack and a mechanic shed by the side of the road, an apartment in a residential complex and tools for a pickle making enterprise operating out of a house.

- One could also argue that this is just the direct contribution of public investment. The indirect contribution, which the economists like to call the ‘multiplier’ effects of public investment, is larger. For example, think of a highway constructed between two cities. It lowers the transportation costs and boosts trade and commerce between the cities. Businesses flourish as they expand and hire more workers. But this indirect effect in India is reduced by huge maintenance costs of infrastructure and other transaction costs like corruption and poor quality of new infrastructure.

- For a more detailed analysis of how policy uncertainty has been increasing and how it severely impacts the returns on private investment, please read these excellent and detailed articles by Shruti Rajagopalan (https://srajagopalan.substack.com/p/an-economic-puzzle-of-the-modi-years?utm_campaign=post&utm_medium=web&triedRedirect=true) and by Arvind Subramanian and Josh Felman(https://www.foreignaffairs.com/articles/india/2021-12-14/indias-stalled-rise).